A brand new play that explores one horrific second prior to now to lift unsettling questions in regards to the future

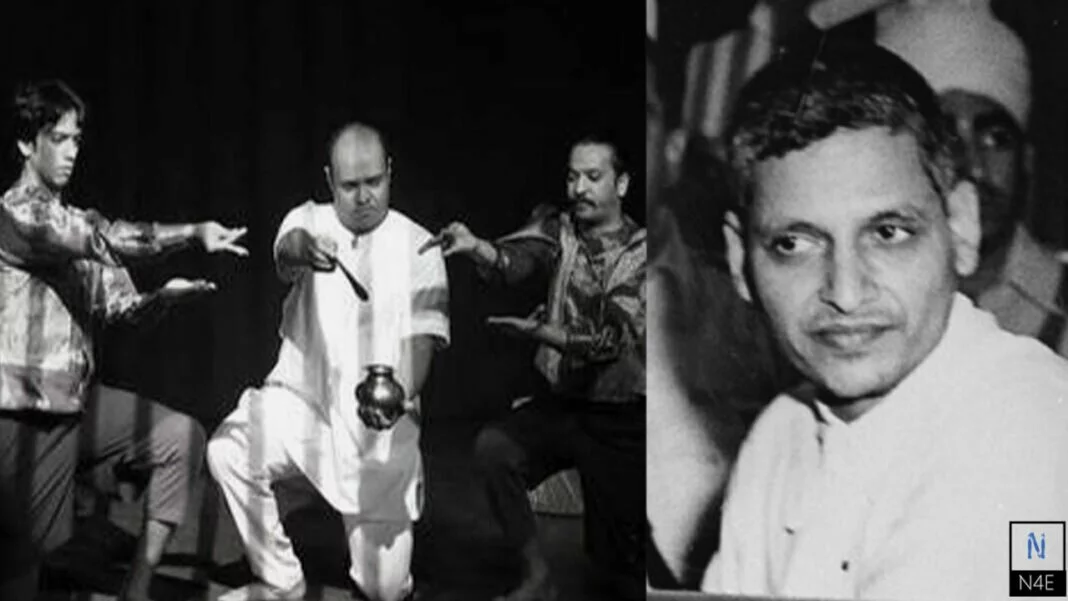

There is one thing deeply troubling about Chennai-based playwright Prasanna Ramaswamy’s new play This is my identify. Long after it’s over, it leaves you with a way of disquiet and lingering insecurity. The 90-minute theatre efficiency that includes a big ensemble solid was not too long ago staged in Chennai to considerably muted response, because of COVID-19.

The play is ostensibly an exploration of the previous — Nathuram Godse’s defence of his assassination of Gandhi. Yet, in doing so, the play primarily raises uncomfortable, deeply unsettling questions in regards to the future.

“While the central figure, Godse, claims that he only performed his duty as a patriot in the act of killing Mahatma Gandhi, the notion of the nation state as against the philosophy of a nation, a land of people, through the several interpolations of fundamentalist acts through history, the discourse moves to reveal the cruel and abysmal ignorance behind the act,” says Prasanna, who has tailored and directed the play, supported by Chennai Art Theatre. “Gandhi is the embodiment of secularism and Godse as a representation of an ideology that is out to destroy secularism and to engage with the perpetrator brings us close to present reality.”

An adaptation of author Paul Zacharia’s Malayalam novella, Ithanente Peru, the play takes the audiences by a “series of soliloquies of Godse ranging from memory, defence, reasoning, fear and so on,” says Prasanna.

Real turmoil

Delivering a shocking efficiency as Godse, actor Sarvesh Sridhar brings to the stage a myriad of eloquent feelings, starting from ecstasy to confusion, from a false sense of peace to a really actual turmoil. Through the play, Godse bases his reasoning on the ideology he grew up with, the ideas towards secularism. In the course of self-enquiry, he revisits what he imagines to be his earlier births. The play ends together with his refusal to signal his identify, claiming that his identify will now be Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

In the tip, all of the actors shed their photos of Godse and are available collectively to ship the highly effective phrases of Kerala’s philosopher-social reformer Narayana Guru on faith and caste, delivered in 1916. “I have no connection whatsoever with any one of the existing religions. All religions are acceptable to me. Everyone needs to observe the religion they like. It is according to the wishes of certain of the Hindus that I have consecrated some temples. Likewise, if followers of other religions like Christians, Muhammedans wish, I am only too happy to do the necessary for them as well. When I say that I have left behind the differences of caste or creed, it only means that I have no special attachment to any of the existing castes or religions.”

In his novella, Zacharia “expands the discourse on Godse’s faith in the singular further by arranging episodes from history — those which happened with few other religions, including Christianity, as parallels,” says Prasanna.

In the play, Prasanna deftly locations some modern components as intertexts in an try to ‘raise a question on the cultural output hydrated by the religious faith and another looking at how texts are turned into political equipment.’ So, if we’ve got Nikhila Kesavan as a ‘commentator’ confronting the dancer in Anita Ratnam about her alternative of mythological characters to expound modern feminism (even calling them as ‘suspended in movement’), we even have Dharma Raman and Sharanya utilizing a discourse in Bhagavad Gita as a software for polarisation.

Dramatic engagement

In the course of those intertexts, Anita presents her dance repertoire as a dramatic engagement with the query of artwork and religion. “These two additional intertexts — one voicing a crucial question on cultural manifestations of a faith, any faith, and the other holding a mirror to the act of art and tradition turned into a weapon by the perpetrator — complete the discourse,” says Prasanna.

That a novella written in 2003 holds extra relevance in the present day than when it was first written, and that it might be efficiently tailored as an intense theatre efficiency is maybe a mirrored image of what the nation has gone by in these years.

“The immediate reason to write the play was a re-reading of Godse’s defence in court. It was a powerful document, and he was so deep-rooted in his belief. That is what fundamentalism and terrorism are all about, whatever the religion,” remembers Zacharia. “In 2003, I do think I started writing on what could happen. I had this eerie feeling that things are changing and not for good. Different forces were coming into play.”

Zacharia thinks the novella is extra related in the present day as a result of the “character of Godse has come into greater prominence today; people are building temples for him. In that context, it is worth taking a look at [the subject].”

For Prasanna, it’s all about interrogating the grimness of actuality with the craft of theatre. “We live in times which call for celebration of secular values, especially in a country like India which has been home to people with very different faiths for centuries. This central idea of secularism has been challenged by those who uphold a singular faith ideology and use power to destroy the multicoloured fabric. I think it helps to cut to a close-up to see clear the right-wing ideology that leverages action.”

The play additionally options Nikhil Kedia and Dharshan Ramkumar doing prolonged Godses and different a number of roles. The authentic rating for the play has been composed by Anandhkumar; the art work is a triptych created by artist Gurunathan Govindan; and light-weight design is by Charles. The play options vocals by Sharanya Krishnan and nattuvangam by Subhasri Vidya.

According to Prasanna, the play breaks, fuses and leaps throughout genres working by the ideas of contact and isolation in the direction of a surreal that may be extra actual. “The play brings the rants of Godse, fluctuating between arrogance, fear, and misled ideas, which takes form through stylisation of not just movement but by multiplication of his character. Perched onto this dark discourse are two distracting questions, one about the body of work that came out of faith and another on how art has always been pliable to power.”

The author is an unbiased Chennai-based journalist.