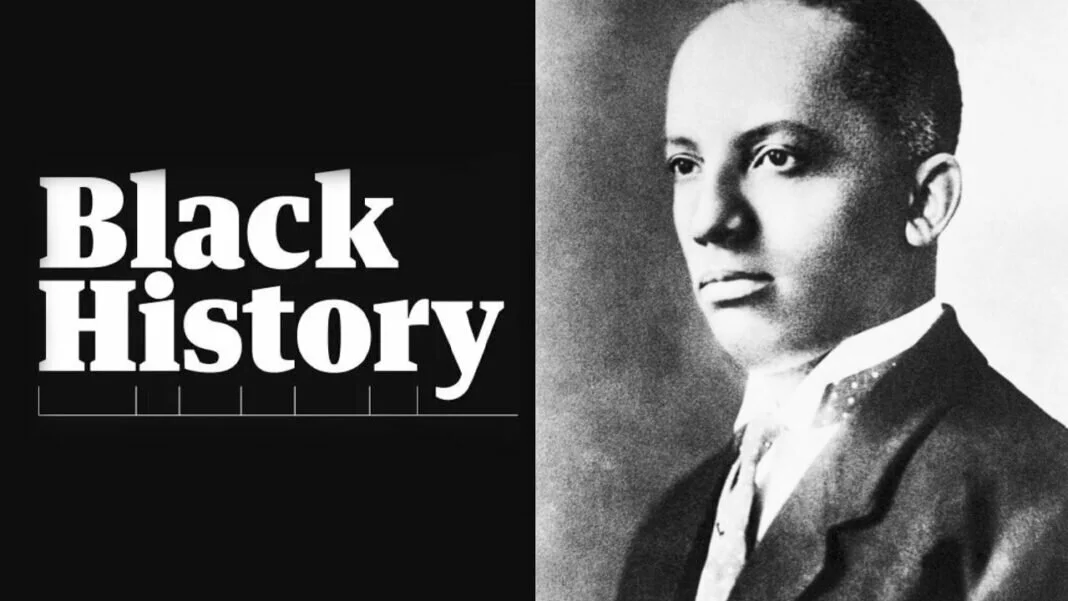

Black History: The man who would become known as the “father of Black history” wrote furiously in his red-brick rowhouse in D.C. At his second-floor “home office” at 1538 Ninth Street NW, Carter G. Woodson led and orchestrated a movement to document Black history, dictating dozens of books, letters, speeches, articles, and essays to promote Black people and their place in American history.

At 12:15 PM on most days, Woodson, who would launch what became Black History Month, met with his staff in the kitchen of the house. He’d give orders and strategize. There was little time to waste. He saw his mission — to correct how White people wrote about Black people, and to place Black Americans at the front and center of American history — as critical.

“If a race has no history,” Woodson wrote, “it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

The house was a center of Black intellectual thought in the country. Woodson published journals and bulletins and wrote books from its rooms. “The Mis-Education of the Negro,” a collection of articles and speeches, was published in 1933. The book has become a classic, advocating for excellence in the education of Black students and demanding that school systems across America correct curriculums designed to deliberately “mis-educate” Black children as well as to promote white supremacy.

“One of Woodson’s objectives was to collect and disseminate knowledge about Black people globally,” said Greg E. Carr, chair of the department of Afro-American studies at Howard University. “The continued relevancy of ‘The Miseducation of the Negro’ was Woodson was really a master of public relations.”

The book, Carr said, has lasting relevancy. “When we read ‘The Mis-Education of the Negro,’ it is as if he is writing from today about topics being debated today,” he said. “Critical race theory, for example.”

Woodson’s 89-year-old work still serves as a template for racial education and a refutation of the belief that systemic racism should be glossed over at a time when the nation is embroiled in bitter debates over how it should be taught in schools. “Woodson flat-out rejects the premise that any American history should resort to an Anglo lens,” Carr said. “In one chapter in the book, he said: I don’t understand why they would devote all this time [in history class] to Europe, descendants of Europe, and not give equal time to the origins of Africans.”

It was said that Woodson, a stern man who works 18-hour days and barely smiles in pictures, was prolific. His bustling house is where he published the Journal of Negro History and the Negro History Bulletin, ran a publishing company called Associated Publishers, and organized the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASALH), which is still active today and has dozens of chapters across the country.

Woodson also established “Negro History Week” in 1926 in this three-bedroom house, which he purchased for $8,000 in 1922. According to the Library of Congress, the Library of Congress designated the week in honor of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass’ birthdays. Woodson described the concept behind the celebration. “It is not so much a Negro History Week as it is a History Week,” he wrote, according to ASALH. “We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in History. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hatred and religious prejudice.”

In 1976, Negro History Week was extended to include the entire month of February. In studying Black history, Woodson’s seminal work was highlighted. “‘The Mis-Education of the Negro’ is probably one of the most important books ever published for African Americans and for African American history,” said W. Marvin Dulaney, president of the ASALH. “The book lays out that African Americans have been mis-educated in our public school systems.”

“The theory of this book was to help Black people understand we come from a greater society,” said Karsonya Wise Whitehead, former ASALH national secretary and an associate professor of African and African American studies at Loyola University Maryland. “And the work we do as parents, teachers and educations should make sure young Black people understand that.”

The creation of Black History Month was motivated by a desire to ensure that Black people understood their past, according to CeLillianne Green, author of “A Bridge: The Poetic Primer on African and African American Experiences.” “If you think you have no history, it’s like being rootless,” she said. “It’s unnatural. If you think your people don’t have history, you can do nothing. The point of Black History Month is so you can understand your history.”

She added, “If you are not teaching the truth, how is the country going to be free?”

C.R. Gibbs, a historian and author, said that 89 years after “The Mis-Education of the Negro,” Woodson’s advocacy for teaching Black history is still relevant. “At a time when we can’t be sure what we will be able to teach, this makes ‘The Mis-Education of the Negro’ even more timely,” said Gibbs, whose work as a historian is featured in the Discovery Channel documentary “Underground Railroad: The Secret History.”

“There are forces in society today who don’t want that kind of insightful, thoughtful history that Carter G. Woodson was chronicling,” Gibbs said. “They don’t want that history to come out. We have to guard against that.” He added, “If there is a book that should be at the top and most useful at this time, it would be ‘The Mis-Education of the Negro.’ Why? Because even in the 21st century, the mis-education of the Negro is still going on.”

Woodson’s house served as an archive for documents sent across the country by Black people. It had a fireproof safe, he wrote in his annual report for 1941, with “1,000 or more manuscripts which will be turned over to the Library of Congress as soon as they can be properly assorted,” including letters from Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, according to the National Park Service.

Woodson’s office and library were located on the second floor of his house. Woodson met with some of the most powerful Black women in history around his desk, including Mary McLeod Bethune and Nannie Helen Burroughs. Zora Neale Hurston’s research and travels that would later inspire her book “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo'” were financed by him using interviews he conducted with Cudjo Lewis. Lewis was one of the last survivors of the illegal transatlantic slave trade from Africa.

According to the Park Service, Langston Hughes was Woodson’s assistant in his home office during the 1920s, when he would become a world-renowned poet instrumental to the Harlem Renaissance movement. “My job was to open the office in the mornings, keep it clean, wrap and mail books, assist in answering the mail, read proofs, bank the furnace at night when Dr. Woodson was away,” Hughes said, according to the Park Service, “and do anything else that came to hand which the secretaries could not do.”

Hughes wrote in February 1945 that America owed Woodson a debt of gratitude. “For many years now he has labored in the cause of Negro history, and his labors have begun to bear a most glorious fruit. Year by year the observance of Negro History Week has grown,” he wrote. “Today the week is observed all across America.”

Hughes informed readers of the Chicago Defender, the prominent Black newspaper, that if they knew of any place in the country where Negro History Week wasn’t being celebrated or wanted material on how to observe the week, they should contact “Dr. Carter G. Woodson, Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, 1538 Ninth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C., and ask him to send you a list of publications and photographs.”

Woodson’s parents were enslaved, and as a child, he worked as a sharecropper and in a coal mine in New Canton, Va. He began high school at the age of 20 and graduated in two years. After attending Berea College in Kentucky and earning a master’s degree from the University of Chicago, he became the second African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University in 1912. (The first was W.E.B. Du Bois.)

Woodson died on April 3, 1950, in a bedroom on the third floor of the house at 1538 Ninth Street NW, in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The house was designated a national historic landmark in 1976. Congress designated it a national historic site in 2003.

“Carter G. Woodson represents for us living history and the importance of knowing whose shoulders we stand on,” Whitehead said. “To be in spaces where he studied and where great minds gathered, to have this real connection to history by being able to touch it, brings history to life.”